A challenge facing information security is our inability to effectively train new analysts. The majority of security knowledge is tacit. We have plenty of practitioners who are good at catching bad guys, but most of them can’t articulate how they do it. I believe that overcoming this issue requires a focus on fundamental thought processes underlying security investigations, which is the foundation of my doctoral research.

Every major thought-based profession has a core construct through which everything is framed. For doctors, it’s the patient case. From this stems the diagnostic process, testing frameworks, and treatment plans. For lawyers, it’s the legal case. From this stems the discovery exercise, the trial, and sentencing. These core constructs are defined as an entities whose whole is greater than the sum of their parts. Each one is a story all its own.

In information security, our core construct is the investigation case. Everything we do is based on determining if malicious activity has happened, and to what extent. I don’t think many would argue this point, but surprisingly, there is very little formal writing out there about the investigation process itself. Many texts gloss over it and merely consider in the sum of its parts, a basic container for related evidence.

I propose that the investigation is so much more.

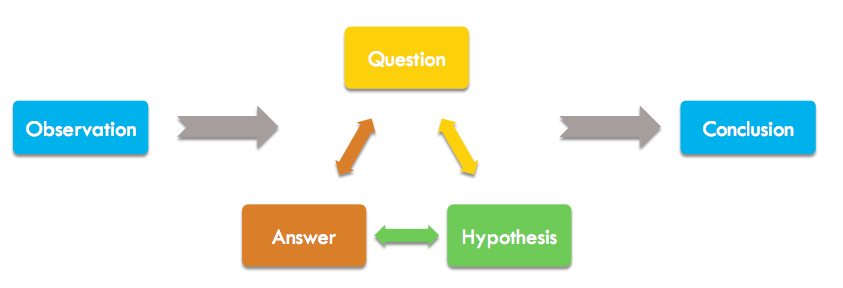

Diagnostic Inquiry

The investigation is at the heart of information security. It is a living, beating thing through which all of our actions are motivated and framed. It is our lens. To understand the investigation you must understand how humans think.

- Perception is not reality. What we perceive as reality and what actually exists are two separate things separated by our ability to interpret sensory input and using higher order reasoning. The process of getting from an initial perception to an accurate depiction of reality is the basis for learning and cognition.

- Learning comes from questioning. Straight from the womb, humans learn by questioning their environment, themselves, and their limits. By asking questions and employing various techniques to find answers we learn to move, walk, talk, and think. These techniques range from simple experimentation to complex reasoning, and can be motivated by primal needs like food and water, or higher order needs like achievement or respect.

- Our biases are always present. There are countless barriers that limit our ability to get from perception to reality. The most dangerous of these is our own mindset and the biases that are inherent to it. Humans are opinionated, and the same questions that drive us toward the pursuit of reality also drive opinions. When those opinions are educated and conscious they are hypotheses, and when none of those conditions are met they are guesses, and more subject to limiting bias.

If you consider this knowledge of human psychology, it begins to paint a picture of an investigation. Instead of trying to create a framework that dictates how investigations should be done, I wanted to take an approach the uncovers how you approach investigations as a form of learning. After all, that’s basically what an investigation is. It’s all about bridging the gap between perception and reality by learning facts. This yields the following definition and method.

“An investigation is the systematic inquiry and examination of evidence and observations in an effort to gain an accurate perception of whether an incident has occurred, and to what extent.”

If this looks familiar to you, that’s because it’s not too different from the scientific method. In a similar manner, the scientific manner wasn’t thought up as some way that scientific discovery should be done; it is an identification how most scientific discovery is done based on how humans learn. Even if scientists don’t intentionally set out to use the scientific method, their subconscious mind is doing it. The scientific method is responsible for the vast majority of scientific discovery. The investigation method is similarly responsible for the discovery of network intruders. It is a process of diagnostic inquiry. We diagnosis anomalous observations through the process of asking questions.

Diagnostic Inquiry contains five parts. I’ll briefly cover them here, although each one is worthy of its own article which will come later.

Observation

Every investigation begins with some observation that arouses suspicion. This is often machine generated in the form of an IDS alert, but could also be human driven in the form of an observation made while hunting. It doesn’t have to be an internal observation, and may come from a third-party notification. The tactics of the investigation are often shaped by the source of the initial observation, but the general process remains the same.

- An observation is usually based on some form of initial evidence.

- An observation can come from anywhere, but should be supportable. Even hunches or gut feelings are supportable when framed appropriately.

- The first goal of the investigation is usually to validate or invalidate the initial observation as the premise of the investigation. If that observation isn’t valid, the investigation may not need to progress.

Question

An investigation consists of a series of questions for which the analyst must seek answers. Based on the initial observation, the overarching questions will likely be some version of “Did a breach occur?” or “Is this malicious?” To answer those questions, more questions must be asked. Answers to one question will usually generate more questions. At any given point, an analyst should be able to articulate what question they’re trying to answer.

- The ability to define good questions increases with experience because expert analysts have a larger pool of heuristics (rules) to draw from.

- Most questions are centered around uncovering relationships, because ultimately it’s the relationships between devices and users that define an attack or breach.

- Newer analysts will frequently begin answer seeking activities without clearly identifying the question they are attempting to answer. This can lead to wasted effort, but usually diminishes with experience.

Hypothesis

You’re usually already slanted towards a specific answer from the moment you define your question, even if you don’t realize it. Your opinion forms based on your mindset, and is shaped by the entirety of your experience, both personal and professional. This is also where bias lives in the investigation process. The ability to articulate a hypothesis is an ideal way to expose bias so that your assumptions can be challenged if necessary. It also provides a clear path to additional questions that can validate or invalidate your hypothesis. Collectively, this leads to better, stronger conclusions.

- Most hypothesis generation is passive and occurs subconsciously. A trick to making this an active process is to form an “I believe” statement for a hypothesis in response to each question. I believe ______ because _______.

- Ideally a hypothesis is an educated guess. If you cannot complete the last half of the because statement, your assumptions may be from a place of bias, inexperience, or an inability to articulate well.

- Every question should provide opportunity for a hypothesis, even if it’s a null hypothesis stating that a scenario isn’t probable.

Answer

The area of investigation most analysts are familiar with is answer seeking. It involves familiar tasks like retrieving, manipulating, and reviewing data. Any time you analytically review data or perform research it’s because you’re seeking an answer to your questions, usually to prove or disprove a hypothesis. Traditionally, newer analysts usually learn answer seeking before anything else which explains why the learning curve is so steep. They are trying to find answers for questions they don’t fully understand.

- The goal of every answer isn’t to solve the investigation, it’s often to provide an opportunity for more questions. The answers you find will only be as good as the question they’re trying to resolve.

- While it may seem logical to seek answers that prove a hypothesis, seeking to disprove a hypothesis is usually a much faster route to better questions.

- Some questions won’t be answerable due to a lack of visibility or not enough data retention. Inability to answer a question is notable, because it might have impact on the investigation later. An unanswered question does not equal an invalid hypothesis.

Conclusion

The conclusion of an investigation is its terminal point. The investigation can terminate as a false positive alert, an acceptable risk, a simple malware infection, or a large breach requiring coordinated incident response. When a terminal disposition has been made, the investigation will contain a series of questions, hypotheses, and answers that uncover a (hopefully) accurate representation of events as they have occurred.

- The strength of conclusions should always be accurately depicted by using estimative language. Certainties should be cited as such and backed up with evidence. Analytic opinions should be weighted based on their estimated certitude and available evidence.

- If the steps that led you to a conclusion are considered carefully and documented well throughout the process, it should ease the burden of citing supporting information when documenting conclusions.

Framing an Investigation

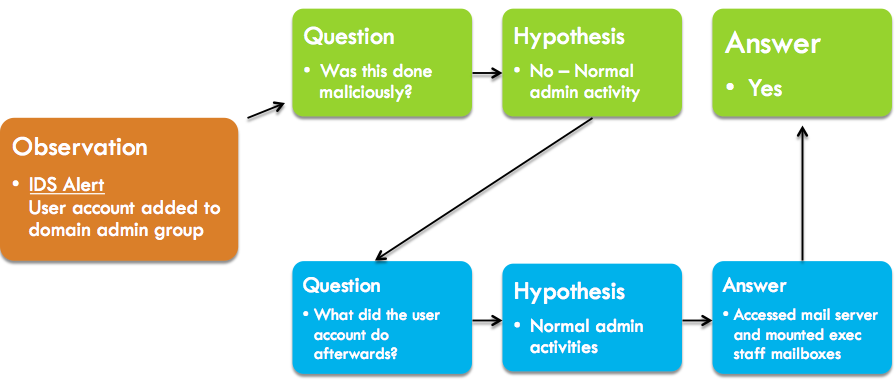

Let’s look at example of what an investigation looks like through the lens of diagnostic inquiry. In this case, our fictional analyst has received an alert from an intrusion detection system.

Initial Observation: IDS Alert – User account was added to a domain admin group

This alert represents activity that might be legitimate, but could be malicious if it was unauthorized. The first question that generally follows an alert of this nature is whether it is malicious or normal activity.

Question 1: Does this alert represent malicious activity?

If the analyst were in a small organization they might be aware of any changes like this that should be occurring. Our analyst works in a very large enterprise, so it’s entirely possible that someone made this change for a legitimate reason without the analyst knowing. Because of this, the analyst believes its legitimate activity.

Hypothesis 1: I believe this is legitimate activity because this is something that happens frequently within the organization.

To answer the initial question, the analyst must prove or disprove the hypothesis. To do this, more questions must be asked. There are a number of routes the analyst could go here, but one many analysts would pursue relates to follow-up actions taken by the user account.

Question 2: What actions did the user account take after being added to the admin group?

Based on the earlier hypothesis that this is normal behavior, it’s likely the hypothesis to Q2 will be similar.

Hypothesis 2: I believe the account participated in legitimate admin activity because it supports hypothesis 1.

Seeking an answer to Q2 should be fairly easily with adequate visibility into your system and network logs. The analyst is able to search through logs fed into his SIEM and determine that the user account in question logged into a workstation, opened Outlook, and mounted several C-level executives mailboxes from the Exchange mail server.

Answer 2: The user account logged into a workstation, opened Outlook, and mounted several C-level executives mailboxes from the Exchange mail server.

The answer to Q2 appears to disprove our hypothesis 2, which in turn disproves hypothesis 1. The activity exhibited by the user account is definitely malicious, and answers our first question.

Answer 1: The actions taken by the user account after being added to the domain admin group are malicious in nature due to unauthorized access to multiple sensitive mailboxes.

At this point, the analyst is confident a breach has occurred, and the investigation can continue with that in mind. This should bring up more questions as the investigation evolves, including:

- Was the user account an existing user account whose credentials were compromised?

- Are there any indicators of compromise on the workstation normally used by the user who owns this account?

- How did the potential attacker gain enough access to be able to promote the compromised account into an admin group?

- How did the user account gain access to the workstation used to mount the Exchange mailboxes?

- Is there any malware installed on the workstation the mailboxes were mounted from?

- Were any other accounts accessed from the system belonging to the owner of the compromised account?

As you can see, what I’ve articulated here is only a fraction of what could be a much larger investigation. The key takeaway is that it provides a very structured, easy to follow timeline of the investigation and how it progressed. This makes it much easier to review the investigation process from beginning to end, and to use this investigation as a teaching tool for novice analysts.

As a Universal Method

Diagnostic Inquiry is a universal construct within information security. While the industry often glamorizes unique subspecialties like hunting and malware analysis, they all fit within the same scope of activities. The method still applies.

For example, consider threat hunting. It follows the same process to bridge the gap from perception to reality. The only difference is that the initial observation is usually human-driven. Instead of receiving an IDS alert or an external notification, the analyst asks broad questions based on their library of experience-derived heuristics. The goal of this questioning is for the answers to generate more questions, or lead to the discovery of evidence that represents malicious activity.

This isn’t to say that subspecialties don’t require unique skill sets. They most certainly do. A hunter is usually someone more experienced because they have a larger library of investigative heuristics to work from, which allows them to be more effective at coming up with questions that can drive the discovery of interesting observations. A novice analyst wouldn’t have nearly as many heuristics to rely on, and their efforts would be less fruitful.

The characteristics of a good analyst will vary based on specialization, but the method is universal.

Why It Matters

Diagnostic Inquiry isn’t provided as a framework. The truth is that this is the method you likely already use to investigate security events, even if you aren’t aware of it. That awareness is key, because it gives practitioners a language to express their knowledge. From this comes more insightful analysis, more clearly identified methods that lead to conclusions, and an ability to teach novice analysts how investigations can be performed through the lens of an expert.

If you walk into a hundred SOCs you will find a hundred ways of documenting investigations. There is no standard, and worse yet, most end up adopting whatever format their tooling provides. What happens is that ticketing systems and wikis end up defining how analysts perform investigations. This is tragic.

If you walk into those same hundreds SOC’s, you’ll also typically only find one way of teaching people how investigations should be done — through on the job observation. While observation-based training is a key component of any training program, an education that is founded entirely on observation is sure to fail. I wouldn’t want a surgeon who skipped medical school and went straight to residency to be operating on me. Sure, they might be able to get the job done, but they’ll be missing the fundamentals that make them flexible and prepared for the inevitable unknown.

This is one significant reason why defenders are so badly outpaced by attackers in information security. Our profession hasn’t gone through its cognitive revolution where we seek to understand how we approach the investigation and it’s components. If we want to get there, understanding human thought and the methods that form the investigation are key. This article seeks to shed light in some of those areas, and certainly the articles to follow will as well.

I’d encourage you to consider the method shown here and think through it as you perform your investigations. What questions are you asking? How are your hypotheses swaying your analysis? How strong are your conclusions? How do you express how you approach investigations? These are all useful questions and are pivotal in your own understanding of the craft, as well as those who will come after you.

Security approach has interacted is sure with resik concept . So the research will be inhanced in case the two approach incorporated togrther

Great article Chris. Much of it validates the way I’ve been training analysts for years. *breathes sigh of relief*. Thanks for posting.

Really nice to see what we do “naturally” explained clearly in a blog post. Nice work!

Really well written and original post. Thank you Chris.