Unwritten social contracts dictate many of the rules of modern employment between the employer and the employee. One of these more common tacit agreements is how long each party expects the arrangement to last.

Traditionally, when an employee went to work somewhere they expected to work there forever. The career arc hopefully involved moving up in responsibility with commensurate pay until reaching retirement. However, this romanticized notion of a lifetime contract isn’t realistic in many modern industries.

Employer-employee social contracts evolve culturally, which means they change much slower than many of the fast-moving industries they exist within. Even though most employers and employees know their arrangement is only temporary, they act as though it’s permanent. The resulting state of cognitive dissonance leads to band-aid retention programs and career-limiting compromises. These problems all stem from a fear of the inevitable question for any worker — “What’s Next?”

In this article, I’ll discuss the lifetime employment mindset and how it drives detrimental retention practices, strategies for better handling “golden handcuff” packages, and thoughts on a better way forward with a tour of duty approach.

The Paradox of a Lifetime Contract Mindset

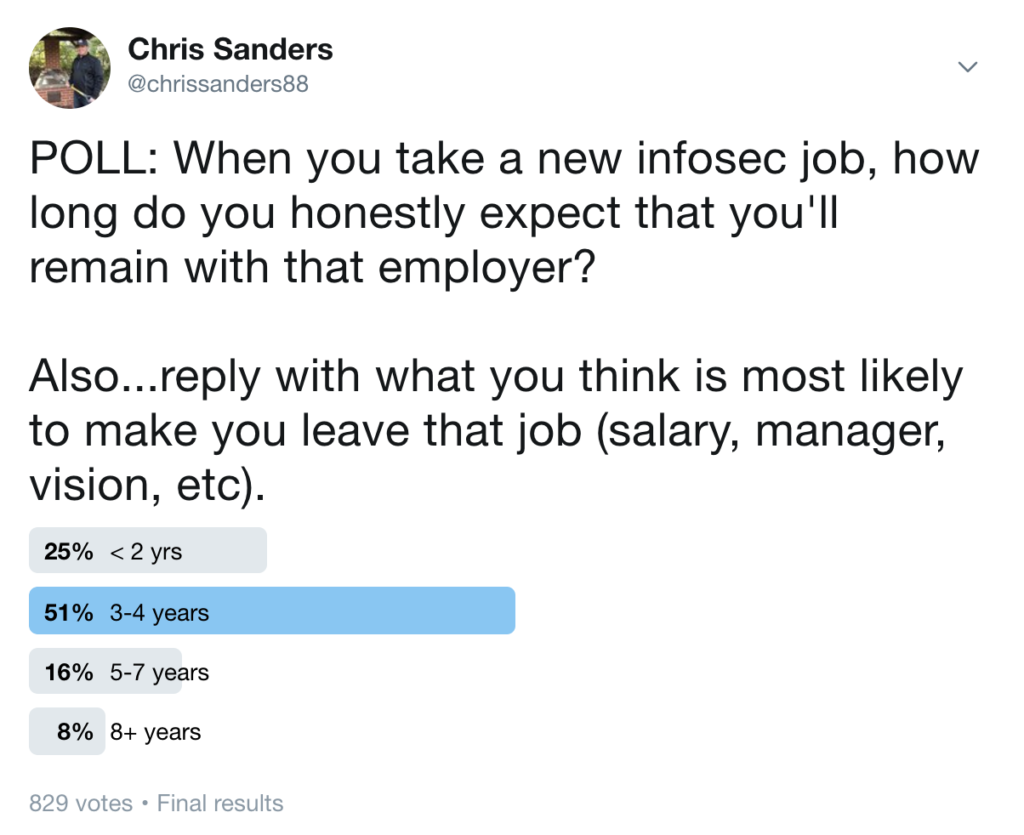

When you take a new job, how long do you honestly expect that you will work for that employer? I recently asked this question informally on Twitter:

Most infosec workers know that whatever their next stop is, it won’t be for long. This sentiment is echoed amongst the broader population. One survey of individuals born between 1977 and 1997 found that 91% of respondents expect to be in their current job for less than three years (Forbes).

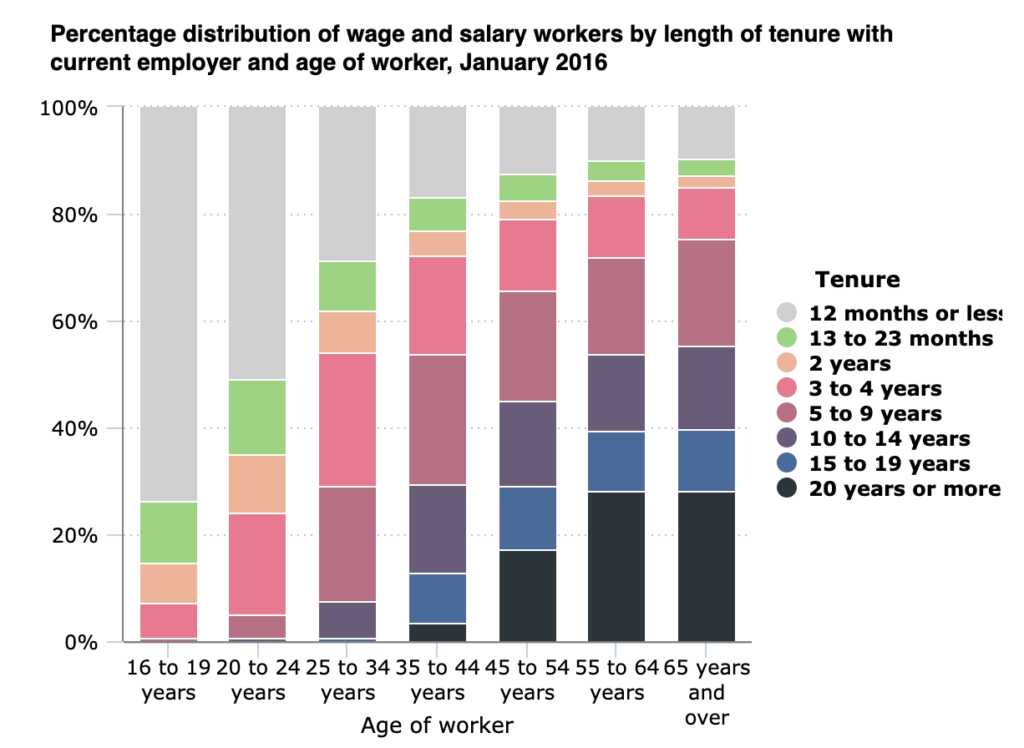

The Bureau of Labor Statistics tells us that the median tenure for workers ages 55 to 64 is 10.1 years versus 4.9 years for 35-44 year-olds and 2.7 years for ages 25 to 34 year-olds (BLS). While you would certainly expect that employment might generally become more steady as a person ages, the broader trend seems to be that society is moving further away from the long-romanticized notion of lifetime employment.

While labor statistics specific to infosec are somewhat lacking (I find many mentioned but few cited), we have seen estimates that the average CISO tenure is less than two years, and the average infosec employee tenure is 2-4 years. Anecdotally, this meshes well with what I’ve seen throughout my relatively diverse career in infosec spanning government contracting, public, and private sectors.

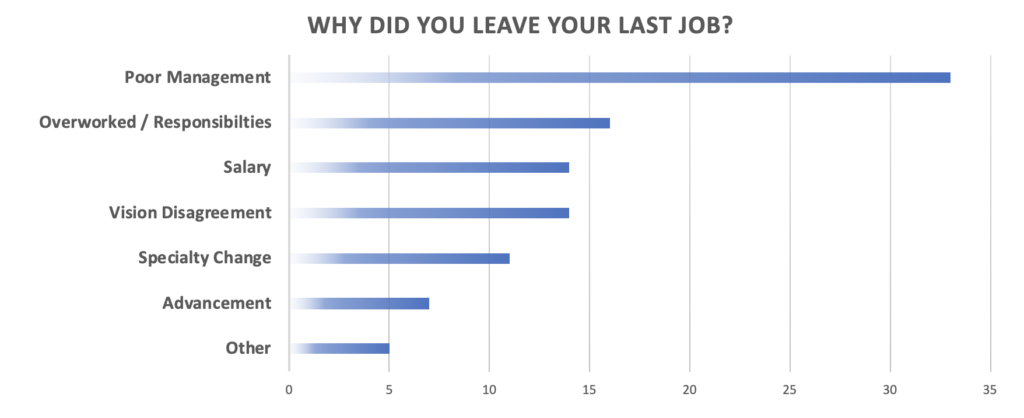

Frequent employment moves occur for a number of reasons: promotion, salary increase, unhappiness with the manager, boredom, lack of educational opportunity or personal growth, a change in specialty, or a desire to have a more tangible impact on the world. While it’s beyond the scope of this article, many of these reasons are more common in infosec due to its unstructured nature and relative immaturity.

Employer Retention and Golden Handcuffs

Employers know that their likelihood of retaining good employees for a long time is low, so they implement strategies to try and keep them longer. After all, it’s in their interest to keep good, motivated employees for as long as they can. Skilled employees with localized knowledge are hard to find, and it’s cheaper to retain an existing employee than it is to hire and train a new one.

A few of the more common retention strategies are:

- Sign-On Bonuses: A cash bonus when you start with a new company. It often has a “clawback provision” that requires you to pay the money back if you leave the company before a specific time duration has elapsed.

- Clawback Bonuses: Very similar to a sign on bonus, but usually awarded to employees who are already with the company.

- Stock Grants: A gift of stock that vests (can actually be sold for real money) over time. These are often stepped, so you might be given a thousand shares of stock with 250 vesting every year for four years.

- Relocation Bonuses: The employer pays your moving expenses with the agreement that you’ll refund the money if you leave before a specific time period.

Each of these strategies comes with some variety of binding agreement centered on retention — this is why they’re often referred to as golden handcuffs.

The problem with golden handcuffs from a psychological standpoint is that their effectiveness is limited to the perceived value of money. We know that everyone values money differently based on their own upbringing and present financial responsibilities. At a broader scale, we know that the emotional-well being provided by money generally peaks between $60k-$75K before significant diminishing returns are observed. Now consider that the average infosec salary is already around $95K; well above where those diminishing returns kick in.

A while back, I did another informal survey asking peers why they had left their most recent infosec gig. As you can see, money was far from the top reported response.

Beyond that, some organizations are willing to cover paybacks that would be incurred by their potential hiring targets. I’ve talked to a few people who were able to get their new employer to either fully pay back a lingering sign-on bonus from a previous employer whose duration terms were not met. If not that, some wrap a prior bonus payback into their new sign-on bonus with similar requirements, essentially carrying it forward.

I’ve seen two common occurrences where golden handcuffs worked to retain employees:

- In delayed-vesting stock grant situations, the employee decides they want to leave but continues working until their next big stock vesting cliff, which might be up to a year later. You can actually observe this happen in larger companies with regular vesting dates. Social media is filled with people from those organizations announcing their new jobs a few weeks after the earnings call.

- In a few cases, I’ve seen people in tight financial situations who accepted clawback bonuses of varying types. They wanted to leave for a better opportunity later, but because they already spent the money and had no ability to pay it back they were stuck.

While these things did help retain employees for longer, it wasn’t beneficial for anyone. For the employee, their happiness plummeted leading to learning stagnation, a slow down in career development, and even feelings of helplessness or depression. For the employer, they realized much less value from the employee whose productivity took a nosedive.

An Employee’s Guide to Golden Handcuffs

Earlier, I mentioned the cognitive dissonance when you operate under the assumption of a lifetime commitment when that is highly unlikely to be the case. However, this dissonance isn’t on the part of the employer. Employers know what’s up — that’s why they have the golden handcuffs. The dissonance is on the part of the employee who tricks themselves into thinking that they will spend the rest of their working life at a single organization despite the likelihood otherwise. It’s no surprise this happens — we want stability and we generally have confidence in our own choices, particularly on something as big as employment. To admit that your next workplace is only a very short term stop while also trying to convince yourself that you should make a change is a challenging proposition.

It’s critical as an employee to recognize the situation you find yourself in. If an organization offers you golden handcuffs there are some things you can do to better prepare yourself for the reality of the situation:

- First and foremost — you never have to accept a bonus. Do your research and be very clear on the terms and conditions tied to the offering and how they relate to your future plans. It can be very hard to look that far into the future, but if you don’t really believe you’ll come anywhere close to meeting the retention requirements you might be better off declining the bonus. Turning down money or stock is never easy, but this might be a great opportunity to negotiate for a higher salary instead.

- If it’s cash-based — don’t spend it until you’ve met the retention requirement. Either put it in a high-interest account or invest it in something relatively stable like an index fund (do your research, I’m not a financial advisor). That way, if you do decide to leave you aren’t hamstrung by the money you’ve already spent. With the right strategy, it may appreciate in value over this time.

- Be prepared for the tax hit. Any time you receive a bonus there are tax implications, so you’re not really pocketing as much as you think you are. This isn’t too complex with cash bonuses but gets more complex with stock. Remember that if you accept a bonus but don’t meet the retention requirements you might end up also out some portion of the taxes you paid as well. A professional tax preparer is cheaper than you think and contracting their services also usually makes them available to answer questions about these scenarios.

- Consider WHEN the bonus is paid. This matters for relocation bonuses, which are often paid upon signing but before moving. If you are moving to a state with a lower income tax rate, you may want to ask the employer not to pay the bonus until you’ve established residency in the new state. This can save you thousands of dollars.

- Ask for the bonus to be pro-rated. It’s reasonable to limit the payback liability through stepped forgiveness rather than a single, far-off cliff. For example, instead of having to pay back the full amount if you don’t stay for 5 years, ask about reducing the payback amount 20% for every year of service. Companies won’t always want to do this, but it’s particularly important for cases when the amount and duration are large.

- Ask for an acquisition clause. You signed up to work for the company that hired you, not the company that buys them. Ask your employer to include a clause that eliminates the clawback provision if the organization is acquired by someone else. Some companies will try to tell you that these provisions aren’t transferable to new ownership anyway if a transferability clause is absent, but it’s worth being explicit about. This is particularly important for small startups that are more likely to be acquired.

A Pragmatic Approach: Tours of Duty

If employers know that you won’t be there for very long and you know that you won’t be there for very long, it’s dishonest to operate under the assumption that employment is a permanent arrangement. Furthermore, it sets everyone up for failure and creates hard feelings when one party is caught by surprise when the other ends the arrangement.

I first learned about the tour mindset in Reid Hoffman’s “The Startup of You“. While I don’t fully endorse the book, this concept stuck with me. A tour of duty (ToD) is a change to the social contract where the employee and employer acknowledge a much shorter expected duration of employment — usually between 1 and 4 years.

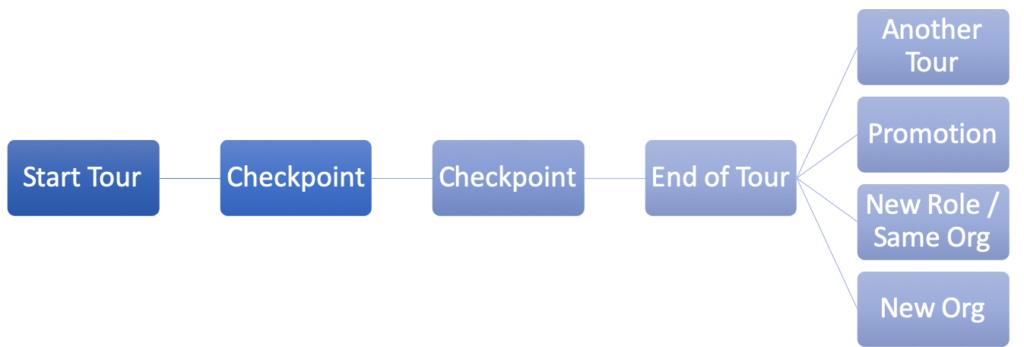

This is different from an actual contract job where the employer has a hard cut off date. When a tour ends HR doesn’t press the ejection seat button on your job, it simply marks a target date for re-evaluation. If everyone is happy and wants to continue then you sign up for another tour. If not, everyone works together to figure out the next steps whether that’s a promotion, another role within the company, or going somewhere else.

The goal of a tour is for the employee to provide as much value to the company as possible while the company also does its best to prepare the employee for their next job.

A tour of duty acknowledges that time is limited and gives the employer and employee the opportunity to make two plans:

- Plan A – Company Goals: These are the things the employee will help the employer accomplish during the tour. This might mean completing a big project, helping drive up or down an important metric, or leaving certain facets of the organization in a better place. These goals aren’t always quantifiable in numbers, but they are observable.

- Plan B – Individual Goals: These are skills that the employer will help the employee learn during the tour. Constant improvement and learning define a career in information security. These skills will prepare the employee for their next job, whatever it might be.

We’ll continue to talk about Plan A and Plan B throughout the rest of this article.

A Tour of Duty Timeline

While the length of a tour might differ, there are steps that must happen to make them work. Here’s a sample tour of duty timeline broken down into some employer and employee milestones.

| Timing | Employer | Employee | Both |

| Interview Process | Make the tour of duty mindset and approach clear | Highlight how you can help the company meet its goals (plan A), and the goals you want them to help you meet (plan B). | |

| First Week | Set concrete Plan A Goals. | Set concrete Plan B goals. | Define a checkpoint schedule. |

| + 6 Months | Review Plan A goal progress | Review Plan B goal progress. Make adjustments based on future plans. | Goals Checkpoint |

| – 6 Months from End | Review Plan A goal progress. Start to define final deliverables | Review Plan B goal progress. Make adjustments based on future plans. Start to consider other jobs if applicable. Feed these requirements into your Plan B goals. | Goals Checkpoint |

| – 1 Month from End | Present a plan for what next steps might include: another tour, another position, promotion, etc. | Begin to finalize a decision about what’s next. | Have the “What’s Next” conversation? |

| End of Tour | If renewing, start back at First Week. |

An Employer’s Guide to a Tour of Duty

If you’re a business owner or manager, adopting this mindset might initially appear to be against your best interest. For all the reasons I mentioned earlier, you likely want to retain motivated employees as long as possible. However, we all know that’s not likely in today’s climate. With that in mind, there are some distinct advantages to a tour mindset.

- Forced Goal Setting: If you know that you’ll only have an employee for 24 guaranteed months, you’ll tend to operate with more purposeful goals in mind. These might not all be set completely from the get-go, but you’ll be more motivated to purposefully hire rather than just loading the books with talent that goes underutilized.

- Predictable Turnover: Because tours end, you have a general idea of when you may need to backfill positions. That’s significantly preferable to a random mass exodus or losing key people at busy times of the year. Keep in mind that in larger organizations, a tour of duty often means employees can leave for new jobs within your same company. So, you can plan to phase folks from one role to another as people naturally move around. Some companies ignore this potential, but it should be welcomed.

- Periodic Check Points: Nothing forces periodic evaluation more than a deadline. Even though a tour deadline is soft, mutual acknowledgment of its existence provides an opportunity to check how you’re meeting Plan A and Plan B goals (mentioned above) and adjust course if necessary.

- Fewer Gimmicks: If you’re not focused on retention through golden-handcuff style bonuses, it decreases the complexity of your HR and finance operations. Even better, you can just pay people more in the first place.

- Employee Satisfaction: Perhaps above all else, employees will appreciate the acknowledgment of reality. Great leaders don’t merely manage; they prepare people for whatever’s next. That’s how you build a legacy and make people want to come work for you. Word travels fast in our relatively small field. A manager who cares about the best interests of their employees beyond the confines of a company’s walls will attract and retain skilled people.

With all those things in mind, there are some tricky considerations about how you approach tours of duty with potential employees. After all, some people are going to be put off by the notion that you’re building a checkpoint into their employment, even if it’s a soft one. There are some things you can do to make this clearer and easier on everyone:

- Be Clear Up Front: You should be open about the tour mindset with prospective employees from the very start of the interview process. If they aren’t on board or are completely entrenched in the idea of lifetime employment they may not be the best fit.

- Set Hard Checkpoints: I’ve already described the benefits of checkpoints, so you need to set and stick to those. I recommend at least every six months.

- Provide Training Opportunities: Tours don’t work if you only focus on Plan A. You have to ensure you’re helping employees meet individual learning goals by providing access to training, whether internal or external.

- Accept the Variable Value of Money: Money means dramatically different things to different people. Everyone’s financial situations vary for reasons you won’t always be able to comprehend. Some people have crippling debt, others are from cultures where it’s traditional to support their parents after a certain age, some people have medical problems, etc. These are all reasons why money now is better than money later, and if you really care about your employees, you need to accept this. Simply pay them more upfront. If you truly want to do something special, consider profit sharing that is paid out based on merit.

- Outline Employee Benefits: Ensure applicants are clear on how tours benefit them. Speaking of which…

An Employee’s Guide to a Tour of Duty

I think it’s much easier for employees to get over the psychological hump of tours of duty over lifetime contracts than it is for the employer. After all, this is an employee-centric approach. A tour mindset provides several benefits:

- Break Points for Life: There’s immense value in taking a step back to evaluate your past, present, and future. A tour of duty provides a time to do that. Rarely in life do we get the opportunity to plan for change. Usually, it’s when we graduate high school or college. This adds several more of those throughout the course of a career. This can be tremendously beneficial to your mental health and help you find what you’re truly passionate about.

- Forced Focus on Goals: If you know that you’ll only be on the job for 24 guaranteed months, you’ll tend to operate with more purposeful goals in mind. These might not all be set completely from the get-go, but you’ll be clear on what’s expected from you. If you’re employer’s on board, they’ll also better utilize your skills.

- A Better Learning Plan: Because you know that you’re also preparing for whatever’s next, you’ll constantly make progress on your learning plan. Eventually, Plan B will become Plan A.

I advised employers to be upfront with employees when they operate under a tour mindset. You might think I would advise you the same, but I’ve spent enough time out in these streets to know that if you tell an employer you are only signing up for 18 months then that’ll probably be the last you hear from them. All is not lost, however, as you can still treat the job as though it’s a tour of duty without deliberately highlighting the transient nature of your tenure. Of course, it’s still better for everyone to be on the same page if possible. Here are things you can do to operate in a tour mindset as an employee:

- Prioritize Salary: Avoid golden handcuffs, because they defeat the purpose of a tour of duty. In this approach, money now is better than money later. If your employer insists, push them for a cash bonus or raise. If they are confused, use this as an opportunity to explain the tour of duty philosophy if the time and climate are right.

- Set Plan A (Company) Goals: Work with your manager and be deliberate about what needs to be accomplished during your tour. Many jobs fail because of a lack of clear goals.

- Set Plan B (Individual) Goals: What do you want to do next? This might change a few times during your tour, but your individual learning plan should always adjust to reflect your next step. Come up with a plan, figure out how to achieve the learning necessary, and pursue it relentlessly.

- Set Checkpoints with Your Manager: This is where you’ll ensure you’re meeting Plan A goals. As you get closer to the end of your tour, this is the time you’ll start to approach the topic of “What’s Next”. At a minimum, plan for one of these six months into your tour and six months from its end.

- Set Checkpoints with Yourself: You should continually evaluate your interests and plans, but also be sure to set hard checkpoints for intense reflection and evaluation. Make time to talk to your family, friends, and colleagues as you assess your happiness. Priories shift dramatically and sometimes it takes outside perspective to realize that.

Conclusion

In this article, I discussed the cognitive dissonance that commonly exists between employers and employees based on the unspoken social contract that employment with one organization is meant to be forever. I also discussed how tours of duty are a more modern form of this social contract.

I want to be clear — a tour of duty mindset isn’t for every person or every company. I fully appreciate that some of you may be holding back vomit as you read this and digress over how Silicon Valley it all sounds. There’s a significant psychological barrier to contend with when you shift to a mindset that your next job won’t be your forever job. That’s not something everybody wants to grapple with quite yet. That’s okay; I get it and I respect it. It’s normal to *want* your next job to be your forever job and to strive for it. After all, hope is the thing that uniquely binds humanity together and seeking the acceptance and security of a forever job is a form of hope.

For those who can make it work, I think the tour of duty mindset provides an approach to employment that can empower organizations and employees and bring about small revolutions in transparency and accountability.

References

- BLS Figures on Retention: https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2016/28-percent-of-workers-age-55-and-over-have-been-with-their-current-employer-20-years-or-more.htm

- Happiness, Income Satiation, and Turning Points Around the World: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-017-0277-0

- Information Security Analyst Salary Information: https://money.usnews.com/careers/best-jobs/information-security-analyst/salary

- Forbes on the Transient Nature of Jobs: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jeannemeister/2012/08/14/the-future-of-work-job-hopping-is-the-new-normal-for-millennials/#6963adc513b8

- Reid Hoffman, Ben Casnocha, and Chris Yeh on Tours of Duty: https://hbr.org/2013/06/tours-of-duty-the-new-employer-employee-compact

- The Startup of You: https://smile.amazon.com/Start-up-You-Future-Yourself-Transform-ebook/dp/B0050DIWHU?sa-no-redirect=1

Thank You! This article was like you knew actually what I needed to hear. I have been struggling with reconciliation between the two notions of long term job (my parents thinking, I’m 41) and ToDs. Having another perspective on this old concept helps me think more clearly on the whole matter. Having come from a previous military career (9.5 yes AD) that was my first “real job” that forced and allowed me to have multiple Tours of Duty I know see how it parallels the information security field. One I’m relatively new to, having only worked in this space for 5 years. Previously, I was an intelligence analyst for the USAF. I’ve had some trouble with conveying my thoughts on this dichotomy to my wife and I think this article will help.

This is a really well-written article. Feel like I’ve lived most of this — and Chris, you filled in the blanks nicely to give a reader the full picture without pulling any punches.

Some cultures don’t support it quite right, but rotating all duties, or as many duties as possible, really helps. Do more than one ToD, but inside the same organization — why leave? Another path is that you come back to the same org later in life, especially in a different role and with greater duties.

Salary is not important, but not every person is in a position at every segment of life to not prioritize it based on other things happening (e.g., parents or children often require reprioritizing financial plans). Get a financial planner to help with income continuation insurance and similar products.

In the part about Why did you leave your last job?, I think that Specialty Change needs to be higher and Poor Management needs to be way lower. How do you think we can change our industry in this direction?