The typical answer to someone who asks how they can break into information security is, well…it depends. While there’s beauty in the notion that someone can find a career in infosec from so many diverse paths, it also represents the ongoing cognitive crisis confronting the industry.

Universities struggle to develop job-ready information security graduates, often leaving new degree-holders to shift their focus to other disciplines like IT support. Those who go the traditional university route have trouble finding security jobs in part because employers know they lack the skills needed to make an immediate impact. Hiring a fresh college graduate is a significant training investment for employers, both in their ramp-up time and the time experienced personnel must devote to on the job training. Many experts in the field encourage aspiring analysts or engineers to pursue traditional computer science degrees or something else while learning infosec concepts on their own. Others encourage avoiding college altogether. In some circles, college degrees are vilified or chalked up as a waste of time.

At the same time, we’ve seen a dramatic increase in the number of private training institutions that have arisen to fill this need. That’s perfectly fine as we expect the market to evolve to meet the needs of the workforce. However, we must acknowledge that the economic drivers behind most private offerings often limit their effectiveness when weighed against what cognitive science tells us about effective learning. The industry correctly figured out that academia wasn’t teaching the right things, but as practitioners pushed academia to the side for that reason they also shed its methods.

In this article, I’ll talk about one of those methods called spaced learning and how private training providers’ departure from it unfavorably affects individual learning and the broader industry.

Spaced and Condensed Learning

Learning something is generally broken out into three phases: encoding, storage, and retrieval. When you perceive information through your senses it’s encoded for processing in your brain so that short term memory can access it. In some cases, that encoded data may be stored in long term memory where later retrieval is possible even after the information departs the spotlight of your attention. That’s a simplified explanation, but it’s proof you’ve learned something if you can remember information later by retrieving it from long term memory.

Memory research tells us that your chance of learning something successfully is heavily influenced by how long you spend learning information, how often the information is repeated, and the frequency and diversity of how you retrieve it. With this in mind, two contrasting teaching methods are worthy of discussion: spaced and condensed learning.

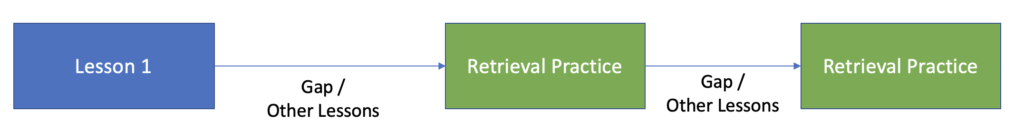

Spaced learning is a pedagogical approach where lessons or topics are broken into small chunks and repeated across multiple learning sessions. Most of your formal education was probably built around the idea of spaced learning. In high school, you went to each one of your classes for an hour or so per day before going to the next one. In college, you probably spent one or two hours in the same class for two or three times per week. In the best scenarios, you were occasionally asked to recall information you had learned previously and apply it to new situations.

Condensed learning is a pedagogical approach where a complete lesson or concept is taught all at once before moving on to something else. Private training providers typically take this approach by offering multiple days or week-long “crash” or “immersion” courses. Each concept you learn likely builds towards the next one in a snowball effect, but the individual concepts themselves are often not revisited directly for the sake of time and progress.

As private training evolved to meet the needs of the market, there are many reasons why these offerings almost exclusively use condensed learning.

Condensed learning is easier to schedule. Security training is specialized enough that it typically doesn’t exist in the same location as the business that wants to provide it to their staff. Organizations must send people somewhere else or bring in an external trainer. It’s feasible to travel once for a week, but it’s not feasible to travel twice a week for a few months.

Condensed learning forcibly removes some distractions. When you’re locked in a classroom with the instructor for an entire day it allows you to dedicate that time to learning without the typical distractions of the office. Some folks prefer off-site training because they feel that they need this separation.

Condensed learning creates an illusion of retention. We are consumers of information and generally believe that as more useful information is thrown at us we are inherently learning more. A condensed schedule provides longer sustained periods of information transfer, or so we think. More on this later.

Condensed learning is profitable. The industry needs training and the market has evolved to provide it in a cost-effective manner for many of the reasons already mentioned. Where demand meets supply there’s an opportunity to generate revenue, and training using condensed learning almost always generates higher profits than alternatives.

While these are perfectly valid reasons for condensed learning to exist, there is one flaw. Condensed learning goes against much of what cognitive science tells us about how effective learning occurs.

The Value of Spaced Learning

If you take nothing else away from this article, know this: An enormous amount of research shows that spaced learning is remarkably more effective than condensed learning.

The goal of learning is to store things in long term memory so they can be retrieved as needed and applied to individual situations you encounter. You want to remember how to use a feature of Burp Suite so that you can apply it during a web app penetration test. You want to remember how HTTP headers are organized so you can figure out what’s happening when you discover malware using HTTP for command and control communication. Learning isn’t just about understanding something as it’s taught to you, it’s about your ability to apply it in situations that matter.

Cepeda et al (2006) performed a meta-analysis of 184 articles spanning nearly a hundred years to summarize the effects of spaced learning. They said:

More than 100 years of distributed practice research have demonstrated that learning is powerfully affected by the temporal distribution of study time. More specifically, spaced (vs. massed) learning of items consistently shows benefits, regardless of retention interval, and learning benefits increase with increased time lags between learning presentations.

You’re more likely to remember the things you learn if that learning occurs in spaced chunks. But, it’s not simply the passage of time and relearning the same concept again that produces increased retention. It’s a combination of retrieval practice, interleaving, and sleep.

Retrieval Practice

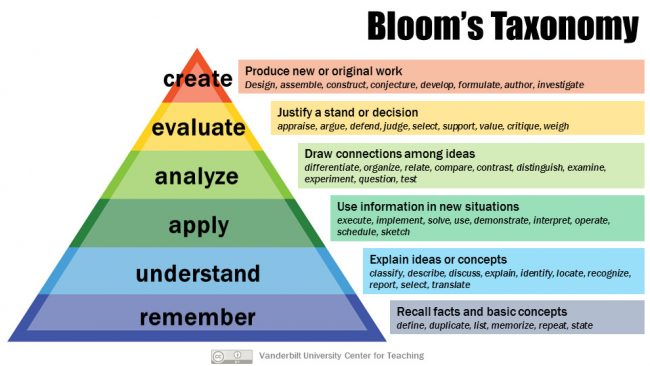

The value of knowledge doesn’t simply lie in remembering facts or gaining a basic understanding of an idea. In information security, like most professions, knowledge becomes useful when it’s applied to problems, used to draw connections among ideas, relied on to evaluate positions, or leveraged to create original work. These tasks represent higher-order thinking as categorized by Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Bloom’s Taxonomy describes a roadmap to knowledge fluency through a hierarchical ordering of cognitive skills. For example, consider how the taxonomy might apply to HTTPS. The most basic level of knowledge helps you remember that HTTPS is encrypted and typically occurs over port 443. From there, you develop an understanding of how HTTPS communication flows between client and server. As you learn more you begin to apply your knowledge of HTTPS communication to individual investigations where the protocol appears. You use this knowledge to analyze evidence and draw connections between network and host-based events and evaluate whether something malicious occurred. Eventually, you may create tools, scripts, or playbooks to process and encapsulate HTTPS-based scenarios.

These tasks don’t merely represent the extent of your knowledge, they represent the journey of your learning. Each time you have the opportunity to retrieve a concept or idea in a new way you inherently strengthen that knowledge, effectively leveling up towards higher-order thinking.

So much focus is placed on getting information into your head that we miss out on getting information out of your head. That’s where retrieval practice comes into the picture. Retrieval practice is a study method based on deliberately recalling information in new and unique ways to increase fluency. Here are a few examples:

- After learning about NTFS and FAT file systems, you participate in a discussion that contrasts and compares their forensic analysis implications.

- After learning about Wireshark features, you complete a PCAP analysis challenge where you can apply those feature towards achieving a solution.

- After learning about how ShimCache artifacts are created, you draw a diagram to represent the process.

- After learning about Suricata signature syntax, you examine rules with syntax errors and fix them.

Retrieval practice can be quite varied ranging from simple discussions to complex labs. The key with each of these examples is that it forces you to retrieve information and apply it in a new way. Spaced learning provides the opportunity for retrieval practice by revisiting similar concepts over and over again, bringing a unique perspective to each repetition while also connecting to newer concepts. This strategy boosts higher-order thinking and application of knowledge.

Interleaving

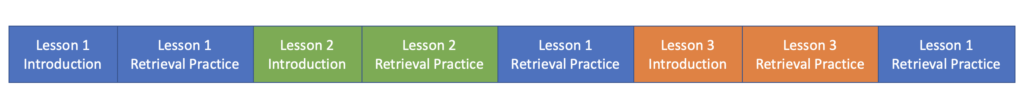

There’s a lot to learn, and spacing doesn’t imply that you stop learning during the spaces between revisiting a topic. Instead, spacing provides an opportunity for interleaving knowledge. Interleaving is a learning technique that mixes together different topics and retrieval strategies.

Roediger and McDaniel (2014) describe a scenario where a baseball player is trying to improve their batting skills. In the first practice scenario, the pitcher throws 10 fastballs, followed by 10 changeups, and finally 10 curveballs. In the second scenario, the pitcher throws the same number of each pitch type, but they are delivered randomly so that the batter doesn’t know what pitch comes next. Which practice strategy do you think works best? If you guessed the second one, you’re correct.

In the first scenario, the batter can get into a rhythm for each pitch type because they’re operating almost exclusively from short term memory; repeating the same action over and over again. In the second scenario, the batter is forced to more broadly approach each at-bat because they can’t predict what pitch comes next. This type of practice mirrors a game setting more realistically while engaging broader thinking for each pitch. The key here is that the interleaving of pitches forces the batter to forget whatever is in their short term memory and re-engage things stored in long-term memory. While it seems counter-intuitive, forgetting (some, but not too much) is the key to learning because it forces retrieval from long term memory.

While the baseball example may not apply to you, the concept most certainly does. Consider learning to search in a SIEM console. In one less-effective practice strategy, you might go through a bunch of examples demonstrating each feature the search tool provides: simple content matches, wildcard searches, exists searches, sub search, regex matching, etc. You perform a few searches using each search feature before moving on to the next topic.

In a more-effective strategy, you get an overview of each of these search capabilities. This time, however, you’re given broad, multi-faceted scenarios and asked to formulate searches for them using the various search features at your disposal. How would you find this type of event log? How would you find this command and control? How would you find evidence that this user’s system was compromised given what you know about another infected host? Weaving these practical scenarios throughout a class at different points forces you to recall information about the search features and apply them to the scenario. This is difficult, but the mental strain of pushing yourself to recall and apply concepts characterizes effective longer-term learning.

Interleaving concepts provides an opportunity for natural spacing between structured recall. At the same time, leveraging related topics provides new and differing lenses through which to re-approach a previously learned concept. In one session you might learn about how evidence of process execution manifests in Windows event logs. In another session, you might learn about how attackers will often disable services that interfere with their goals. When it comes time to re-approach process execution in the event log, you might now connect these ideas and consider how an attacker might disable the event logging service or selectively remove incriminating logs from evidence. Your perspective is constantly shifting, and the combination of spaced learning and interleaving lets you use this to your advantage.

Sleep

Most of us recognize the obvious benefits sleep has for our physical bodies, but many fail to recognize the cognitive benefits sleep provides as well. The brain requires energy just like any other part of the body, so sleep provides it an opportunity for rest. However, some magical things happen in the brain while we sleep that go beyond our dreams.

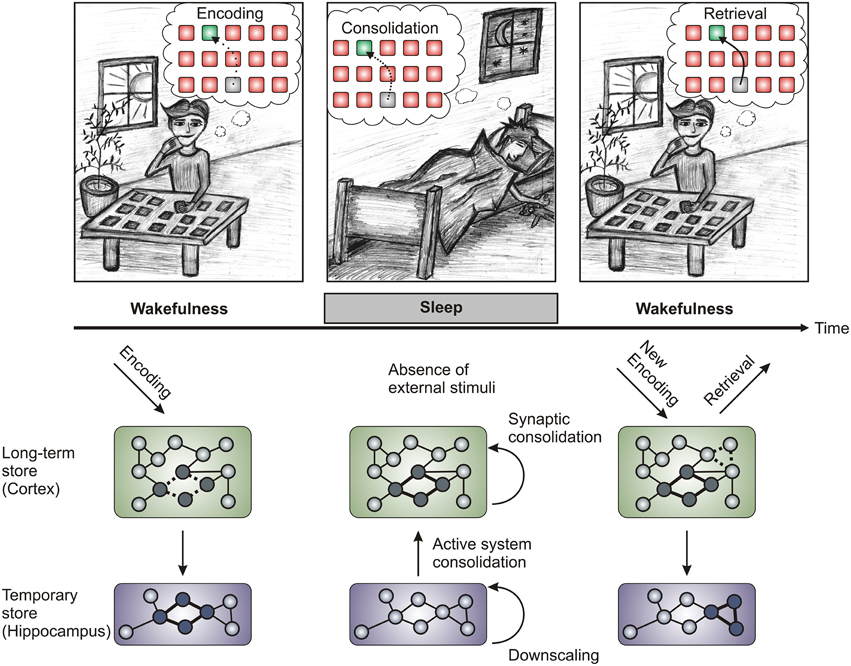

While we sleep, the brain works to optimize itself through the process of consolidation. I liken this process to defragmenting a hard drive. During the day, information is written to disk wherever it can go the fastest. This process optimizes for speed of encoding. The defragmentation process reorganizes scattered data into contiguous chunks so that it can be accessed faster. This process optimizes for later retrieval. While not a perfect analogy, the same thing happens in your brain while you sleep. The pathways for information retrieval are optimized so that information can be approached more readily and with a new perspective. This happens through a lot of physiological processes like neural pruning and strengthening of myelin sheaths connecting neurons.

I’ve seen the positive effects of sleep first hand in my Investigation Theory class. This class features several investigation lab scenarios, including some that are difficult and designed to force analysts into roadblocks. In a couple of labs, I’ll notice that students submit answers over and over again within a single day, getting the solution wrong each time. They revisit evidence sources several times and eventually give up. The next day they log back in and get the correct solution on the first try. The fresh perspective provided by the time away and the neural “defrag” that happens at night produces favorable results.

Spaced learning provides more opportunity for sleep between retrieval practice. While that’s a simple concept, it’s immensely powerful.

The Illusion of Fluency

When I’ve had discussions about spaced learning research with colleagues, I’m commonly told, “But, I learn a ton when I’m in a week-long course!” or “I think I would know if I wasn’t actually retaining most of what I’m taught.”

There’s a problem with these sorts of statements and it relates to your ability to assess your own learning efficacy. In general, research shows that individuals are not great are predicting how much they will learn in a given scenario or assessing how much they did learn in a session. This makes things difficult for educators because you can’t simply rely on course feedback or reviews to determine if students are actually learning and retaining information in the way that you desire.

Typically, learning is measured through assessment. But, that assessment must be spaced to test for longer-term retention and higher-order thinking. These are challenging propositions because such assessment is often logistically and operationally complex. For my Investigation Theory class, I had to build a custom web-application to achieve the level of assessment required. This level of effort isn’t feasible in every situation.

I want to be clear on another point: when I say that spaced learning is better it doesn’t mean condensed learning is completely useless. Inefficient learning is often better than no learning. The common phrase used to describe crash courses is “drinking from a firehose”. If you’ve ever tried to drink from such a hose you know that you’ll probably alleviate your thirst, but more water finds its way to the ground than into your stomach.

Taking your learning seriously means you must recognize that just because something boosts learning in the short term doesn’t mean it will have an equivalent long-term effect. While you usually feel like you’re learning so much in those week-long crash courses, you’re certainly retaining much less of it than you imagine. That is the illusion of fluency. There’s value in understanding that your learning efficacy self-evaluation is flawed.

Moving Forward with Spaced and Condensed Learning

We know that condensed courses are significantly less effective for retention when compared to their spaced counterparts, so why aren’t more training providers building courses with this in mind? I think two things are at work here.

First, most industry infosec teachers are practitioners first and educators second. That isn’t fundamentally a bad thing, but very few people who teach information security courses actually study the cognitive science of learning or pedagogy. They’re exclusively focused on the content rather than the delivery. Thus, failure to incorporate spaced learning concepts into training is more a crime of ignorance than anything else. Now, don’t get me wrong…I don’t think every person who decides to teach a course here or there should go get a teaching degree. But, there’s immense value in studying the science and craft of the thing you’re doing, particularly if that thing is your livelihood and you care about furthering the industry.

The second factor goes back to the reasons I mentioned earlier in the article. Condensed courses are easier to schedule, often more appealing to paying students, and generate higher profits. Often times, the best learning outcomes are not consistent with the highest profits and this simply isn’t a tradeoff many companies are willing to make.

There are some creative solutions to better leverage the principles of spaced learning within the context of non-traditional education.

When I started my company, I consciously chose to design all my courses with spaced learning in mind. For example, my Investigation Theory course is a full week of material, but I know that students will miss out on many of the learning opportunities if I choose to cram it into five days. So instead, I leverage a one or two-day live class along with an online component that the student enrolls in after we finish our time together. The live class serves as an introduction to the key concepts of the class, incorporates several labs with opportunities for live feedback, and builds around multiple retrieval practice exercises. While the live class occurs all at once, the online courseware comes with a spaced learning plan. The key is that the retrieval exercises are woven through the live and online classes alike, and can continue to be used once a student completes both. If someone only chooses to take the online version of the course, they start with the spaced learning plan from day one and build on their knowledge using retrieval practice as they go. While online training has some drawbacks compared to live training, it can excel at providing opportunities for spaced learning.

If you’re reading this as an industry training provider, I realistically don’t expect you to feverishly start working to redesign your curriculum, but small and large opportunities exist to enhance any training course using these principles. I described my approach as an example, but there are plenty of others as well. This includes:

- Designing courses to include diverse practice retrieval exercises

- Providing practiced retrieval exercises for your students to leverage after the class

- Interleaving complementary topics

- Shortening the live component and leveraging recorded online material

- Shortening the live component and leveraging live online remote sessions

- Providing follow on study materials with spacing recommendations

- Scheduling shorter class days with bigger breaks

If you’re reading this as a practitioner, student, or another consumer of infosec education, know that there’s value in understanding the efficacy and limitations of your own cognition. Learning isn’t nearly as simple as existing in the same room where facts are recited. It’s an active process that requires focused engagement, building the right connections between concepts, and opportunities to practice and recall information. If educators don’t provide these opportunities for you, then you have to provide them for yourself. There are a few ways to do this, broadly speaking:

- Write down key concepts and revisit them every few days. Try to recall everything you remember about the concept and verbalize it or write it down. Flash cards make this easier.

- Attempt to visualize complex workflows or procedures. Actually take the time to draw a diagram, process, or concept.

- Reteach what you’ve learned to someone else, even if that someone else is your dog.

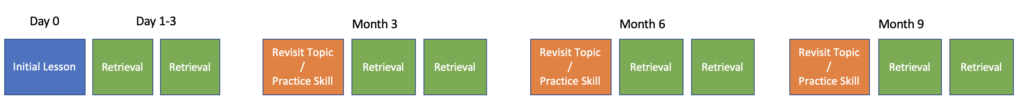

- Schedule time after a class to recall and relearn important concepts — actually put it on your calendar. Research indicates that you’ll find maximum value by recalling a concept three times when learning it initially (within a few days) and revisiting/practicing the concept completely it three times at widely spaced intervals (a few months apart).

Conclusion

In this article, I described the principle of spaced learning and why it’s preferable to the condensed learning format that’s so pervasive in technical industries. I believe many of the problems facing information security that define our cognitive crisis are rooted in education failures.

I started this article out vocalizing criticism of universities. I want to be clear that we need universities to be successful for many reasons that go beyond this purpose of this article. As it stands, industry teaches the right things while academia teaches with the right methods. Enhancing collegiate information security education provides the opportunity to combine practitioner-sourced curriculum with academia-sourced delivery and that has the potential to be a transformative experience. Getting there doesn’t necessarily need a concerted, global effort. It can happen at the individual university level with the right sort of open-minded leaders and self-sacrificing practitioners.

Our education challenges are fixable, and we can look to cognitive science and other industries to better our approaches. While a full course correction may require a concerted effort, spaced learning strategies are something that can be implemented by individual educators and learners. A grassroots effort to engage favorable learning techniques has the power to be transformative.

Sources

- Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives. Vol. 1: Cognitive domain. New York: McKay, 20-24.

- Cepeda, N. J., Pashler, H., Vul, E., Wixted, J. T., & Rohrer, D. (2006). Distributed practice in verbal recall tasks: A review and quantitative synthesis. Psychological bulletin, 132(3), 354.

- Dudai, Y., Karni, A., & Born, J. (2015). The consolidation and transformation of memory. Neuron, 88(1), 20-32.

- Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory into practice, 41(4), 212-218.

- Brown, P. C., Roediger III, H. L., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick. Harvard University Press.

- Rohrer, D. (2012). Interleaving helps students distinguish among similar concepts. Educational Psychology Review, 24(3), 355-367.

- Rohrer, D., Dedrick, R. F., & Stershic, S. (2015). Interleaved practice improves mathematics learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(3), 900.

- Stickgold, R. (2005). Sleep-dependent memory consolidation. Nature, 437(7063), 1272.

- Walker, M. P., & Stickgold, R. (2004). Sleep-dependent learning and memory consolidation. Neuron, 44(1), 121-133.

- Feld, G. B., & Diekelmann, S. (2015). Sleep smart—optimizing sleep for declarative learning and memory. Frontiers in psychology, 6, 622.

- Kornell, Nate, and Robert A. Bjork. “A Stability Bias in Human Memory: Overestimating Remembering and Underestimating Learning.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 138, no. 4 (2009): 449–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017350.

- Zechmeister, Eugene B., and John J. Shaughnessy. “When You Know That You Know and When You Think That You Know but You Don’t.” Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society 15, no. 1 (January 1980): 41–44. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03329756.

- Metcalfe, Janet. “Cognitive Optimism: Self-Deception or Memory-Based Processing Heuristics?” Personality & Social Psychology Review (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates) 2, no. 2 (April 1998): 100. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0202_3.

- Kang, S. H. K. (2016). Spaced Repetition Promotes Efficient and Effective Learning: Policy Implications for Instruction. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732215624708

- Pashler, H., Rohrer, D., Cepeda, N. J., & Carpenter, S. K. (2007). Enhancing learning and retarding forgetting: Choices and consequences. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14(2), 187–193. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03194050

- Rawson, K. A., & Dunlosky, J. (2011). Optimizing schedules of retrieval practice for durable and efficient learning: How much is enough? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 140(3), 283–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023956

- Smolen, P., Zhang, Y., & Byrne, J. H. (2016). The right time to learn: mechanisms and optimization of spaced learning. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience; London, 17(2), 77–88. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.augusta.edu/10.1038/nrn.2015.18

Special thanks to Stef Rand, for help compiling research for this post.

Great article,

I do agree with your position based on personal experience. I took a SANs class this past winter, 6 days and lots of evening time to get through the material. I understood the concepts but didn’t really feel I knew the material as well as I wanted at the deep detail level. I took a couple months break, prepped for the exam a 1-2 hours a night over several weeks. My mark was into the 90s with 100% on the practical elements.

Thanks for all that you do for the security community and keep writing, I have a couple of your books and they are category killers.