I’ve spent the majority of my career thinking about how to build a better mousetrap. More to the point, better methods to catch bad guys. This includes everything from writing simple IDS signatures, to developing detection systems for the US Department of Defense, to helping build commercial security software. In these roles I mostly focused on network security monitoring, but there are quite a few other facets of computer network defense. This includes malware reversing, incident response, web application analysis, and more. While these subspecialties are diverse and require highly disparate skill sets, they all rely on analysis.

Analysis is, more or less, the process of interpreting information in order to make a decision. For network defenders, these decisions usually revolve around whether or not something represents malicious activity, how impactful and widespread the malicious activity is, and what action should be taken to contain and remediate it. These are decisions that can literally cost companies millions of dollars as we saw in the 2013 Target breach, or even eventually result in a loss of human life, which something like Stuxnet in 2010 could have yielded. Clearly, analysis is of incredible importance as it is a determinate phase of the decision making process. If that is the case, then why do we spend so little time thinking about analysis? Before we dive into that, let’s take a look at how we got here.

Evolutions Past

My experience is mostly grounded in network security monitoring, so while this article appeals to many areas of computer network defense, I’m going to frame it through what I know. Network security monitoring can be broken into three distinct phases: collection, detection, and analysis. These take form a something I refer to as the NSM Cycle.

Figure 1: The NSM Cycle

Collection is a function of hardware and software used to generate, organize, and store data to be used for detection and analysis. Detection is the process by which collected data is examined and alerts are generated based on observed events and data that are unexpected. This is typically accomplished through some form of signature, anomaly, or statistically based detection. Analysis occurs when a human interprets and investigates alert data to make a determination if malicious activity has occurred. Each of these processes feed into each other, with analysis feeding back into a collection strategy at the end of the cycle, which constantly repeats. This is what makes it a cycle. If that last part didn’t happen, it would simply be a linear process.

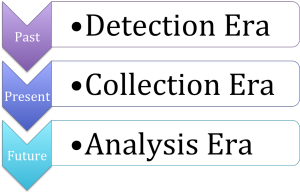

While the NSM cycle flows from collection to detection and then analysis, this is not how the emphasis we as an industry has placed on these items has evolved. Looking back, the industry began its foray into what is now known as network security monitoring with a focus on detection. In this era came the rise of intrusion detection systems such as Snort that are still in use today. Organizations began to recognize that the ability to detect the presence of intruders on their network, and to quickly respond to the intrusions, was just as important as trying to prevent the intruder from breaching the network perimeter in the first place. These organizations believed that you should attempt to collect all of the data you can so that you could perform robust detection across the network. Thus, detection went forth and prospered, for a while.

Figure 2: The Evolution of NSM Emphasis

As the size, speed, and function of computer networks grew, organizations on the leading edge began to recognize that it was no longer feasible to collect 100% of network data. Rather, effective detection relies on selectively gathering data relevant to your detection mission. This ushered in the era of collection, where organizations began to really assess the value received from ingesting certain types of data. For instance, while organizations had previously attempted to perform detection against full packet capture data for every network egress point, now these same organizations begin to selectively filter out traffic to and from specific protocols, ports, and services. In addition, these organizations are now assessing the value of data types that come with a decreased resource requirement, such as network flow data. This all worked towards performing more efficient detection through smarter collection. This brings us up to speed on where we stand in the modern day.

Era of Analysis

While some organizations are still stuck in the detection era (or worse yet, in the ancient period with a sole focus on prevention), I believe most organizations currently exist somewhere in the collection era. In my experience, the majority of organizations are just entering that era, while more mature organizations are in a more advanced stage where they’ve really developed a strong collection strategy. That begs the question, what’s next? Welcome to the analysis era.

Graduate anthropology students at the Kansas State University recently began a study surrounding the ethnography of a typical security operation center (SOC). Ethnography refers to a systematic study of people and culture from the viewpoint of the subject of the study. In this case, the people are the SOC analysts and the culture is how they interact with each other and the various other constituents of the SOC. This study had some really unique findings, but one of the most important to me was centered on the prevalence of tacit knowledge.

Tacit knowledge, by definition, is knowledge that cannot easily be translated into words. The KSU researches were able to quickly identify that SOC analysts, while very skilled at finding and remediating malicious activity, were very rarely able to describe exactly how they went about conducting those actions.

“The tasks performed in a CSIRT job are sophisticated but there is no manual or textbook to explain them. Even an experienced analyst may find it hard to explain exactly how he discovers connections in an investigation. The fact that new analysts get little help in training is not surprising. The profession is so nascent that the how-tos have not been fully realized even by the people who have the knowledge.”

If you’ve ever worked in a SOC then you can likely related to this. Most formal “training” that occurs for a new analyst is focused on how to use specific tools and access specific resources. For example, this might include how to make queries in a SIEM or how to interface with an incident tracking system. When it becomes time to actually train people to perform analysis, they are often relegated to shoulder surfing while watching a more experienced analysts perform their duties.

While this “on the job training” can be valuable, it is not sufficient in and of itself. By relying solely on this technique we are not properly considering how analysis works, what analytic techniques work best, and how to educate people to those things. Ultimately, we are doing an injustice to new analysts and to the constituents that the SOC serves.

Thinking about Thinking

One of the positive things about this analysis problem is that we are by no means the first industry to face it. As a matter of fact, many professions have gone through paradigm shifts where they were forced to look inward at their own thought processes to better the profession.

In the early-to-mid 1900s, the medical field transitioned from an era where a single physician could practice all facets of medicine to an era where specialization in areas such as internal medicine, neurology, and gastroenterology were required in order to keep up with the knowledge needed to treat more advanced afflictions.

Around the same time, the military intelligence profession underwent a revamp as well. Intelligence analysts realized that policy and battlefield disasters of the past could have been avoided with better intel-based decision making and began to identify more structured analytic techniques and working towards their implementation. This was required in order to keep up with a changing battle space and an evolving threat.

Similar examples can be found in physics, chemistry, law, and so on. All around us, there are examples of professions who had to, as a whole, turn inwards and really think about how they think. As we enter the era of analysis, it is time that we do the same. In order to do this, I think there are a few critical things we need to begin to identify.

Developing Structured Analytic Techniques

The opposite of tacit knowledge is explicit knowledge. That is knowledge that has been articulated, codified, and stored. In order for the knowledge possessed by SOC analysts to transition from tacit to explicit we must take a hard look at the way in which analysis is performed and derive analysis techniques. An analysis technique is a structured manner in which analysis is conducted. This centers on a structured way of thinking about an investigation from the initial triage of an alert all the way to the point where a decision is made regarding malicious activity having occurred.

I’ve written about a few such techniques already that are derived from other professions. One such method is relational investigation, which is a technique taken from law enforcement. The relational method is based upon defining linear relationships between entities. If you’ve ever seen an episode of “CSI” or “NYPD Blue” where detectives stick pieces of paper to a corkboard and then connect those items with pieces of yarn, then you’ve seen an example of a relational investigation. This type of investigation relies on the relationships that exist between clues and individuals associated with the crime. A network of computers is not unlike a network of people. Everything is connected, and every action that is taken can result in another action occurring. This means that if we as analysts can identify the relationships between entities well enough, we should be able to create a web that allows us to see the full picture of what is occurring during the investigation of a potential incident.

Figure 3: Relational Investigation

Another technique is borrowed from the medical profession, and is called differential diagnosis. If you’ve ever seen an episode of “House” then chances are you’ve seen this process in action. The group of doctors will be presented with a set of symptoms and they will create a list of potential diagnoses on a whiteboard. The remainder of the show is spent doing research and performing various tests to eliminate each of these potential conclusions until only one is left. Although the methods used in the show are often a bit unconventional, they still fit the bill of the differential diagnosis process.

The goal of an analyst is to digest the alerts generated by various detection mechanisms and investigate multiple data sources to perform relevant tests and research to see if a network security breach has happened. This is very similar to the goals of a physician, which is to digest the symptoms a patient presents with and investigate multiple data sources and perform relevant tests and research to see if their findings represent a breach in the person’s immune system. Both practitioners share a similar of goal of connecting the dots to find out if something bad has happened and/or is still happening.

Figure 4: Differential Diagnosis

I think that as we enter the era of analysis it will be crucial to continue to develop new analytic techniques, and for analysts to determine which techniques fit their strengths and are most appropriate in different scenarios.

Recognizing and Defeating Cognitive Biases

Even if we develop structured analytic techniques, we still have to deal with the human element in the analysis process. Unfortunately, humans are fallible due to the nature of the human mindset. A mindset is, more or less, how someone approaches something or his or her attitude towards it. A mindset is neither a good thing nor a bad thing. It’s just a thing that we all have to deal with. It’s a thing we all have that is shaped by our past, our upbringing, our friends, our family, our economic status, or geographic location, and many other factors that may or may not be within our control.

When dealing with our mindset, we have to consider the difference between perception and reality. Reality is grounded in a situation that truly exists, and perception is based on our own interpretation of a situation. Often times, especially in analysis, a gap exists between perception and reality. The ability to move from perception to reality is a function of cognition, and cognition is subject to bias.

Cognitive bias is a pattern or deviation in judgment that results in analysts drawing inferences or conclusions in a manner that isn’t entirely logical. Where as a concrete reality exists, an analyst may never discover it do to a flawed cognition process based on his or her own flawed subjective perception. Those are a lot of fancy psychology words, but the bottom line is that humans are flawed, and we have to recognize those flaws in our thought process in order to perform better analysis. In regards to cognitive bias, I believe this is accomplished through identifying the assumptions made during analysis, and conducting strategic questioning exercise with other analysts in order to identify biases that may have affected the analysts.

One manner in which to conduct this type of strategic questioning is through “Incident Morbidity and Mortality.” The concept of an M&M conference comes from the medical field, and is used by practitioners to discuss the analytic and diagnostic process that occurred during a case in which there was a bad outcome for the patient. This can be applied security analysis in the same manner, but doesn’t necessarily have to be associated with an investigation where discrete failure occurred. This gives analysts an opportunity to present their findings and be positively and constructively questioned by their peers in order to identify and overcome biases.

The flawed nature of human thinking will ensure that we never overcome bias, but we can minimize its negative impact through some of the techniques mentioned here. As we enter the era of analysis, I think it will become crucial for analysts to begin looking inward at their own mindset so that they can identify how they might be biased in an investigation.

Conclusion

As an industry we have been pretty successful at automating many things, but analysis is something that will never be fully automated because it is dependent upon humans to provide the critical thinking that can’t be replicated by programming logic. While there is no computer that can match the power of the human brain, it is not without flaw. As we inevitably enter the era of analysis, we have to refine our processes and techniques and convert tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge so that the complex problems we will continue to face can be solved in faster and more efficient manner. Ultimately, the collection and detection era are something that we own, but it is entirely likely that a lot of the analysis era will be owned by our children, so the groundwork we lay now will have dramatic impact on the shape of network security analysis moving forward.

I talk in much more detail about several of the things discussed herein Applied Network Security Monitoring, but I also have several blog posts and a recent presentation video on these topics as well:

- BSides Augusta Presentation – Defeating Cognitive Bias and Developing Analytic Technique: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VHeSsvM1x78&list=UU4PBNDLlS4d75MP0xxcukGA

- Chris Sanders Blog – Differential Diagnosis of NSM Events: http://chrissanders.org/2012/01/differential-diagnosis-nsm/

- Chris Sanders Blog – Information Security M&M: http://chrissanders.org/2012/08/information-security-incident-morbidity-and-mortality/

- Applied NSM Book: http://www.amazon.com/Applied-Network-Security-Monitoring-Collection/dp/0124172083/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1410974776&sr=8-1&keywords=applied+nsm

- Argus Lab – Bringing Anthropology into Cybersecurity: http://www.arguslab.org/anthrosec.html